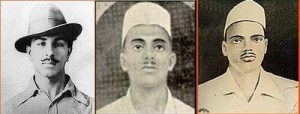

Bhagat Singh in Our Times: Upholding the Revolutionary Legacy

Bhagat Singh’s Letter to the Second LCC Convicts

[ On March 22, the Second Lahore Conspiracy Case convicts, who were locked up in Ward Number 14 (near condemned cells), sent a slip to Bhagat Singh asking if he would like to live. This letter was in reply to that slip. ] March 22, 1931

The desire to live is natural. It is in me also. I do not want to conceal it. But it is conditional. I don’t want to live as a prisoner or under restrictions. My name has become a symbol of Indian revolution. The ideal and the sacrifices of the revolutionary party have elevated me to a height beyond which I will never be able to rise if I live…

Yes, one thing pricks me even today. My heart nurtured some ambitions for doing something for humanity and for my country. I have not been able to fulfill even one-thousandth part of those ambitions. If I live I might perhaps get a chance to fulfill them. If ever it came to my mind that I should not die, it came from this end only.

I am proud of myself these days and I am anxiously waiting for the final test. I wish the day may come nearer soon

As Shahadat Saptah comes to an end, we commemorate the heroic lives of those like Bhagat Singh and his comrades who have become symbol of revolution. We remember the brief, incandescent lives of those like the revolutionary poet Paash martyred on 23 March, 1988 and Chandrashekhar Prasad, former JNUSU president-martyred in Siwan on 31 March, 1997- who lived among the struggling people and were committed to this struggle unto the last. We remember the courage of the countless women and men of our country who overcame their fears, who sacrificed themselves to the cause of true independence, and who gave birth to dreams of equality that still live on.

As Shahadat Saptah comes to an end, we commemorate the heroic lives of those like Bhagat Singh and his comrades who have become symbol of revolution. We remember the brief, incandescent lives of those like the revolutionary poet Paash martyred on 23 March, 1988 and Chandrashekhar Prasad, former JNUSU president-martyred in Siwan on 31 March, 1997- who lived among the struggling people and were committed to this struggle unto the last. We remember the courage of the countless women and men of our country who overcame their fears, who sacrificed themselves to the cause of true independence, and who gave birth to dreams of equality that still live on.

In the life and death of Bhagat Singh, in particular, we find an inspiration for our times and a guide to the struggles ahead. In the world that surrounds us and the issues that confront us, his words and acts acquire particular depth and meaning.

A new meaning to patriotism

Bhagat Singh’s political awakening began at the time of the horrific Jallianwala Bagh massacre where innocent people were surrounded and shot down in cold blood. Over time, as his involvement, with revolutionary politics grew, he grew also in courage and confidence.

Bhagat Singh as remembered by Ajoy Ghosh (later General Secretary of the CPI)

In 1925 like a bolt from the blue came the Kakori arrests. Most of our leaders were in prison within a few weeks… One day in 1928, I was surprised when a young man walked into my room and greeted me. It was Bhagat Singh but not the Bhagat Singh that I had met two years before. Tall and magnificently proportioned, with a keen, intelligent face and gleaming eyes, he looked a different man altogether. And as he talked I realized that he had grown not merely in years. He was now, together with Chandra Shekhar Azad, the leader of our party. He explained to me the changes that had been made in our program and organizational structure.

We were henceforth the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association with a socialist state in India as our avowed objective. We talked the whole night and as we went out for a stroll when the first streaks of red were appearing in the grey sky, it seemed to me that a new era was dawning for our party. We knew what we wanted and we knew how to reach our goal.

Through the struggles he participated in and led, Bhagat Singh gave a new meaning to patriotism. The old cry of Vande Mataram was replaced by the slogan of revolution — Inquilab Zindabad — which he was among the first to proclaim. At the centre of his definition of patriotism were the people of the country. Love for the country became defined as love for its people. He keenly followed the struggles of peasants and workers and insisted that without establishing the dominance of workers and peasants, the national movement would not bring true independence for India. The capitalists, the traders, the princes and big landlords (who were such firm friends of Gandhi); he viewed with the deepest suspicion, arguing that they could only be treated as unreliable friends, if not sworn enemies, of Indian independence.

The nature of the ruling classes

While appreciating the mass mobilization that came with the Gandhian struggle, Bhagat Singh also identified the class character of the Congress and warned that Gandhi’s politics consciously discouraged against any attempt to politicize the working class. He spoke, in fact, of the dangers of setting up a rule by the ‘brown sahibs’ that would merely replace the imperialist rule with another mask, and where the domination of the overwhelming majority of Indians, the workers and peasants, would continue uninterrupted. He stated also that in order to challenge imperialism we must demolish the domestic basis of foreign rule – feudal forces and capitalist collaborators, the props and supporters of imperialist domination.

Where the Congress was afraid to voice the demand for complete independence, where Gandhi openly and repeatedly condemned the revolutionaries, Bhagat Singh and his comrades were unafraid and raised the battle cry: Inquilab Zindabad!

Critique of Gandhian Leadership

“I have said that the present movement… is bound to end in some sort of compromise or complete failure.

I said that, because in my opinion, this time the real revolutionary forces have not been invited into the arena. This is a struggle dependent upon the middle class shopkeepers and a few capitalists. Both these, and particularly the latter, can never dare to risk its property or possessions in any struggle. The real revolutionary armies are in the villages and in factories, the peasantry and the labourers. But our bourgeois leaders do not and cannot dare to tackle them. The sleeping lion once awakened from its slumber shall become irresistible even after the achievement of what our leaders aim at. After his first experience with the Ahmedabad labourers in 1920 Mahatma Gandhi declared: “we must not tamper with the labourers. It is dangerous to make political use of the factory proletariat.” (The Times, May 1921). Since then, they never dared to approach them. There remains the peasantry. The Bardoli resolution of 1922 clearly depicts the horror the leaders felt when they saw the gigantic peasant class rising to shake off not only the domination of an alien nation but also the yoke of the landlords.

It is clear that our leaders prefer a surrender to the British than to the peasantry….”

The War that exists at the heart of our ‘democracy’

In Bhagat Singh initial writings, there is an inclination towards anarchism and revolutionary terrorism, but he was quick to recognize and grasp the superior revolutionary essence of Marxism. He spoke of the indispensable need for an organized communist party and the centrality of a communist politics for independence and socialism. He emphasized the proper combination of all forms of struggle and prepared a draft revolutionary programme that was marked by a consistent and comprehensive revolutionary approach.

The India of Bhagat Singh’s dreams was no ram rajya, nor an idealized world of milk and honey. He warned against the terrifying dangers of communal politics and spoke in no uncertain terms against the brutal realities of caste oppression.

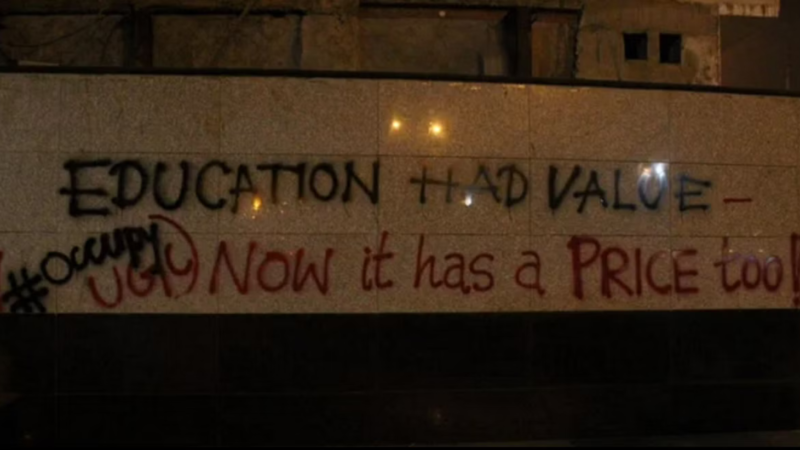

The India that we live in today is no longer a British colony and the sun has long set on the British Empire. It is, however, the land of the brown sahibs that Bhagat Singh warned against. 70% of our people live on less than 20 rupees a day, but our rulers are far too busy attending banquets organized by the US President, leader of the biggest imperialist power in the world. Our sovereignty has been mortgaged to foreign interests. Love for the country has been redefined as ‘love for the corporates’. Vast enclaves of land are being given over as tax-free havens of corporate loot and plunder. When people suffer, the state turns a blind eye; when they protest, it turns a deaf ear. A state of war has been declared: it goes by the name of ‘Operation Green Hunt’ whose targets are the poorest people: the dalits and the adivasis of our land. The Indian state today is as unafraid as its colonial predecessor to shoot down people when they raise the flag of protest.

From Bhagat Singh’s last “Petition to the Punjab governor”:

“Let us declare that the state of war does exist and shall exist so long as the Indian toiling masses and the natural resources are being exploited by a handful of parasites. They may be purely British Capitalist or mixed British and Indian or even purely Indian. … All these things make no difference. … The war shall continue.

It may assume different shapes at different times. It may become now open, now hidden, now purely agitational, now fierce life and death struggle. It shall be waged ever with new vigour, greater audacity and unflinching determination till the Socialist Republic is established and … every sort of exploitation is put an end to and the humanity is ushered into the era of genuine and permanent peace.”

The face of freedom

Yet Bhagat Singh lives on in the struggles of our times and the cry of “Inquilab Zindabad” still resounds. Beyond the films, beyond the statues in parliament, beyond the attempts of India’s ruling class to subvert Bhagat Singh’s revolutionary legacy, his memory endures. It has lived on in Kayyur and Punnapra-Vayalar, in Tebhaga and Telengana, in Naxalbari, Srikakulam, Bhojpur and Nandigram.

Bhagat Singh’s nationalism began with the students and the youth. He urged that they should go deep among the masses, to the colonies of workers and hamlets of the rural poor. For all those of us who wish to fight for an Anti-imperialist and pro-people patriotism, Bhagat Singh is the face of that freedom. For those of us who wish to raise the voice of protest against imperialist agendas, against corporate loot, against draconian laws, against caste violence, religious fundamentalism and patriarchy, Bhagat Singh provides us energy and inspiration.

We remember also the words of Com. Chandrashekhar, who responded to a question asked to him during the JNUSU Presidential debate with the fearless reply: ‘Yes, I have ambitions. My ambitions are to live like Bhagat Singh and die like Che Guevara!’

To speak of Bhagat Singh-Sukhdev-Rajguru, to speak of revolutionary poet Avtar Singh Paash, to speak of Chandrasekhar is to reclaim our history, to make it our own, to declare this country is ours; it does not belong to imperialist capital or its indigenous agents. It is to declare that while we are witness to the suffering of our struggling people, we shall also bear witness to their liberation!

Hello colleagues, how is all, and what you wish for

to say concerning this article, in my view its truly awesome for me.